It may raise a few eyebrows when I confidently state that, for their fateful voyage to the frozen regions, HM ships

Erebus and

Terror were almost certainly equipped with refrigerators.

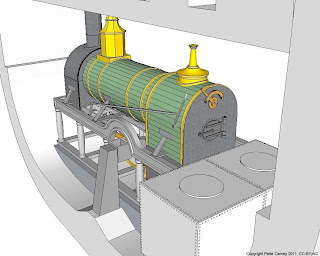

It is also a break with long held consensus, and a volte-face from my previous position, to suggest that the railway locomotive boilers fitted to these ships were modified to boil seawater instead of freshwater.

I'll start by explaining that in the context of early Victorian engineering the word refrigerator was used to refer to what is now called a heat-exchanger. The illustration below, from 1828, shows an example of the 'shell and tube' variety. The hot liquid to be cooled was passed through the array of small tubes while the cooling water flowed around them in the casing. A typical usage was in brewing - to cool the wort down to fermentation temperature after boiling.

Early nineteenth century heat exchanger

Early nineteenth century heat exchangerI began to suspect that the boilers used sea water while thinking about the water consumption of the engines.

Captain Frederick William Beechey made the first proposal to fit auxiliary steam engines to

Erebus and

Terror with the proviso that they should only be used when there was a flat calm and the ice floes were no longer pressed together by the wind.

Beechey wrote "The openings in the ice are generally of short duration, perhaps for eight or twelve hours only."

Samuel Brees'

statistics for the Rennies' engines include the information that the tender's 3.3 tons of water was sufficient for 1.87 hours operation. This equates to 21.2 tons in 12 hours.

The

Terror's tanks held 6000 gallons or 26.8 tons so operating the engine for 12 hours would use 80% of the ships water, supposing that the tanks were brim full to begin with.

Alternatively the full capacity of

Terror's tanks could sustain the engine for a little over 15 hours.

Fresh water is not difficult to find in an Arctic summer as melting snow forms ponds on ice flows but there would be no guarantee when the weather would allow it to be collected.

If fresh water from the ships' tanks were relied on for the boilers there would be a strong possibility that there would not be enough water on board to fully exploit the rare opportunity of an opening in the ice without endangering the crews lives.

Merely getting so much water out of the tanks in such a short time would be difficult. The ships had numerous separate tanks, most of which held around two tons, with stores piled on top of them. Merely getting at the apertures involved laboriously shifting stores around so that a hose from a force pump could be inserted.

Another useful nugget of information is found in the "Particulars of Steamships", in the National Archives.

The entry for

Terror reads:

"Machinery & Boilers complete in every respect

On the 1st trial speed of the Terror was 3.6 knots per hour by Massey's log

with the disadvantage of river water priming the boilers it is expected the speed will be 3 1/2 knots per hour."

National Archives, crown copyright waived for non-commercial use.

National Archives, crown copyright waived for non-commercial use.The entry for

Erebus reads:

"Machinery & boilers Reported to be complete,

on the 1st trial. speed of the "Terror" was 3.6 knots per hour by Massey's log

with the disadvantage of river water priming the boilers, the speed is expected to be 3 1/2 knots per hour"

National Archives, crown copyright waived for non-commercial use.

National Archives, crown copyright waived for non-commercial use.The

Terror's speed trial is mentioned in the entries for both ships, which is perhaps another pointer that the engines were identical in each ship. Erebus, being a foot wider in the beam, would be expected to be slower.

The suggestion of using river water is a clear hint that the ships were equipped to use the water they floated in to feed their boilers. No officer in their right mind would have contemplated contaminating their ship's drinking water tanks with the filth which flowed in "the common sewer of London" - the Thames.

SALT:

I suspect that the widespread belief that the boilers could have only used fresh water is based on the assumption that they would have suffered from excessive corrosion if they had used seawater.

Using seawater certainly did cause greater corrosion. A typical lifespan of a ship's boiler using seawater was only around five years while a similar boiler on land using fresh water could easily last for twenty years. This would not be an issue during the very limited time in which the expedition's engines were expected to operate.

Around the time of the planning of the Franklin Expedition there was

lively debate as to whether iron or brass was the best material for the tubes of ships' boilers.

Brass tubes conducted heat better and were resistant to scaling while iron tubes were more resistant to overheating and avoided galvanic corrosion.

A

specification for paddle steamers issued by the Admiralty in January 1844, and

another for screw steamers issued in September 1845, both included instructions for the tenders to include alternate costings for tubular boilers with iron tubes and with brass tubes.

More immediately dangerous than corrosion was the problem of increasing salt concentration.

A build-up of salt could cause a boiler to 'prime' or boil over, sending a mixture of water and steam to the cylinders. Worse, a boiler filled with excessively saline water could develop an insulating crust of insoluble calcium salts (essentially plaster of Paris) on the boiler tubes, diminishing the flow of heat to the boiler water and causing the tubes to fail through overheating.

In 1824 Henry Maudslay and Joshua Field had patented

a method of changing water in boilers to prevent the deposition of salt and other substances.

In addition to the normal feedwater pumps common to every steam engine, the engine was equipped with what became known as 'brine pumps' which expelled a small quantity of hot supersaline water from the boiler in proportion to the quantity of seawater pumped in, thus allowing the salt concentration to remain constant. To avoid wasting heat, the hot water expelled was passed through a heat-exchanger or 'refrigerator' to transfer its heat energy to the incoming sea water.

The

royal yacht Victoria and Albert (launched April 1843) had engines by Maudslay's complete with their system of brine pumps and refrigerators, and that system was also stipulated in both of the Admiralty's specifications mentioned.

CONCLUSION:Franklin's ships were fitted with the best, most up-to-date technology of the day, including brine pumps and refrigerators (heat-exchangers). They used sea-water in their boilers.

It seems that studies of the Franklin Expedition have suffered from almost as many false trails as the searches for the Expedition itself.

Hopefully this will be the year that Parks Canada find some hard evidence to measure these speculations against.